Les escenes. 25 Years after. Scene 2

Les escenes: 25 Years after

Scene 2

12.02 — 10.03.2019

Opening: Tuesday February 12, 7 pm

David Bestué / Carles Congost / Lucía Egaña / Daniel Jacoby / Gustavo Marrone / PLOM / Alex Reynolds / Julia Spínola / Marc Vives

The first scene of this exhibition was not a birthday piñata. The voids punctuating it and the minimal gesturalism of its works served as a form of resistance and a counterpoint to the grandiloquence of anniversary, context and generation exhibitions. This second scene changes the tone and opens itself up to a playful entanglement with works in which literary, cinematographic and architectural imaginaries are contorted.

PLOM performance: Tuesday, February 26, at 7.30 pm

SCENE 2

The first scene of this exhibition posed a challenge, a problem: the difficulty of mapping out the arts scene in this city. As usually happens at the beginning, the first scene simply serves to situate the starting frame: the celebration of 25 years of La Capella’s dedication to emerging art. The key topic of the first scene was “How to start?” The six inaugural works of the exhibition pointed to six different ways of getting off the ground and opening up a horizon of expectations.

However, something else is expected from a second scene: laying the foundations for a narrative, beginning to weave a story. But this is a project that unfurls from threads and not from warps and wefts. This exhibition does not know of narratives. Something else is woven here: a set of mutual understandings between objects (works of art) and other characters that, until June, will tread the boards of La Capella.

If you have been here before, you will already be familiar with some of these characters. At the entrance to the exhibition, Fardo (2018) by Julia Spínola (Madrid, 1979) remains on scene. This piece is a block made from a tonne of pressed cardboard: an amalgam of matter and time that seems to get denser around this object, as if we were looking at a cross-section of the Earth’s crust with its different geological strata, or at a slice of our own skin, which is similarly stratified.

The drawings and paintings by Gustavo Marrone (Buenos Aires, 1962) allow people to pass through them as if they were portals to other worlds and times like, for example, the 1990s in Barcelona, the time when La Capella was founded. But they are also signs that give us a clue to something else. His works therefore marked an official start, but they also tested the vanishing points towards sensitive subjects of the present day: the body, sexuality, language and self-referentiality. His two new productions – La evidencia and Nada tiene fin – examine the passing of time. Firstly, through a highly ambiguous sentence that is magnified in the middle of the room; secondly, through an installation made from 150 gossip magazines that, beyond everything that has happened in the past 25 years, unashamedly displays the unhealthy and unsubstantial happiness of the monarchy, the nobility and the powers that be from 1994 to 2019.

Melodramas (1998) by Marc Vives (Barcelona, 1979) also provides a clue to something. This artist’s book is one of the few works that cuts across all the scenes. Its protagonism is not that of a character, but instead of a stage prop. A mysterious object whose function is to arouse suspicion and raise eyebrows in its path. It is a device for creating intrigue: something that Hitchcock would refer to as a “McGuffin”. Within the book we find clues that lead us to other clues and, by so doing, they weave an entangled narrative that resists the urge to take a stable form.

There is a sculptural version of this narrative entanglement in the work by Daniel Jacoby (Lima, 1985). Sidney is the name of a series of sculptures treated like a fictional character. To narrate his character’s adventures and misadventures, Jacoby builds modular assemblies from socks, cotton clothes and haberdashery. The end-results are figures of a vaguely anthropomorphic nature that, in some cases, seem like disjointed bodies and, in others, like bodiless joints. But Jacoby’s objects can also be read as oblique sentences, fragments of a language whose syntax we do not know but is begging to be deciphered… unsuccessfully, of course.

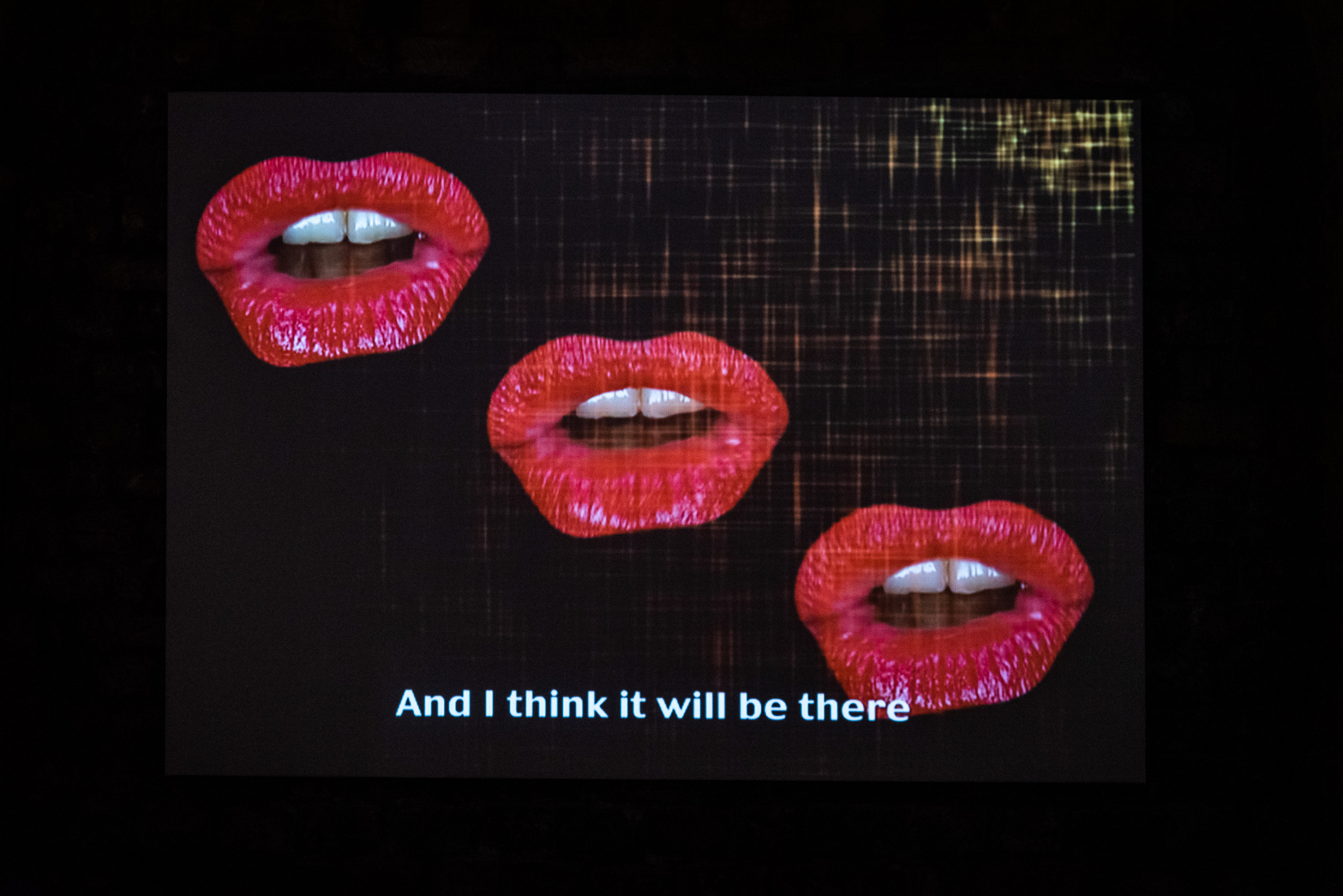

In comparison to Jacoby’s sculptures, the drawings by Lucía Egaña Rojas (Münster, Chile, 1979) are another way of doing things in which the discourse becomes contorted. The textile-textual entanglement of Jacoby’s works is transformed in her works into a carnal-textual one. Her Pajas mentales are a notebook in which it is no longer the discursive content of a book that is transcribed, but instead the physical-carnal reaction it provokes. In the words of the artist: “You also read with your hand, you read with your cunt.” The drawings are electrocardiograms of reading. They are recordings of readings situated to begin with in the body itself, embodied readings, twisted readings that distance themselves from the strictly verbal and call into question the primacy of language-related aspects. For this second scene, the artist has added five previously unseen drawings to the five with which she started scene 1.

Partway between tenderness and bodily horror, the intimist portrait and genre cinema, Alex Reynolds (Bilbao, 1978) presents Como si fuera viento (2018). A film that was shot among friends and almost accidentally – “playing at films,” say the credits – while the artist was spending her summer holiday camping on the Galician coastline. Filming took place during the summer disarray, and film editing was a meticulous and laborious job after seeing how the images and the voices could call upon one another and be arranged accordingly. Somewhat like the dramatics of this exhibition. Twisting cinematographic codes, Reynolds adopts the fascinated gaze of a child and takes astonishment to its ultimate consequences when faced with two of the most basic drives: food and sex. The formative periods of Jacoby and Reynolds took place in Barcelona, and like Jacoby, Reynold’s work falls within a process of critical review of conceptual practices. It seems difficult not to read her recent work as a challenge to that paradigm marked by the primacy of language-related aspects.

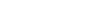

A similar language-related tension is what spurs the production of David Bestué (1980, Barcelona). His work negotiates the irresolvable tension between body and discourse, verb and matter, poetry and sculpture, architecture and performance. Included in the exhibition are examples from the collection of posters that Bestué produced specifically for La Capella after the publication of his book Historia de la Fuerza (2017). This series presents an oblique guide via the major milestones of public works engineering in Spain. Meanwhile, Un Mystique determinado (2003) by Carles Congost (Olot, 1970) offers a caustic and scathing parody of the romantic figure of the genius. Based on songs by the Barcelona-based electropop group called Astrud, Congost’s videos take ownership of the codes of a rock opera to bring some of the key questions of aesthetic philosophy up to date around issues like the meaning of “creation”, the function of art and the social perception of the artist.

On 26 February, PLOM – one of the most indefinable and extreme projects by Pau Magrané Figuera (Reus, 1984) – will present the performance AREA 51 House Party. In his words, it is “an appropriationist massacre of the best 51 dance anthems of late 2018 on Máxima FM, whose visual equivalent would be a 4K HD film on a 50-inch screen that would explode over and over again and be rebuilt in 3D graphics made from tiny fragments of glass and plastic.”