Mera aparença

To disappear

When in an interview published a few years ago, Umbert Eco affirmed that if "the hundred years ago the story was going on a bike, today it was going by car >>, as well as echoing the importance that it had for our culture a dynamic concept as well as speed, we were also auguring consequences that have not only been confirmed but have acquired a magnitude that exceeds what we imagined. That is to say:

- That the speed at which events happened would accelerate the rhythm of work history;

- That the satisfaction of contemplating learning would be replaced by a more adventurous and ephemeral pleasure;

- That the immediacy of this pleasure would move us away from what, even less than a hundred years ago, he had taught us to live, for example, in nature;

- That we would form part of a society that would ignore the future.

From those words to date there have not been more than ten years and if during the period of time that Eco spoke to us the story had changed as a means of locomotion and men had begun to move away from the most contemplative experiences today History goes to the speed of light and our moments of satisfaction can count on the fingers of one hand. And I wonder: it is not possible that, despite being accelerated, we have time to stop for a while, breathe a bit of air, contemplate what we have before us and, if we wish, re-enter the world again without believing Do we enter into another galaxy? Is not contemplation possible when speed and acceleration determine the rhythm of our existence? And if so, what can bring us contemplation when the effectiveness of any activity is valued more for the goals achieved, not because of the intensity of the experiences lived? Frankly, I do not know. But what I believe, on the other hand, is that the aesthetic experience of contemplation could well be a type of experience capable of reconciling with the acceleration all those who experienced it. On the one hand, because it induces to forget oneself; on the other, because it does not ask for understanding, or adjudications of transcendence, anxieties, or sympathies, and finally, because the pleasure felt does not derive from the subject but from the things that are observed, immersing ourselves in and learning her beauty.

Consequently, in a moment like the present one in which much of the artistic creation bases the interest of its proposals in the active participation of the spectator to obtain a complicity that rarely roots and thrives, the works that better can To appease the pernicious effects of the inevitable and, to some extent, logical acceleration (which, as everything else, also affects art) are just those other works, which, far from demanding the active participation of the viewer, respect The right you have to look without being awkward if you do not collaborate in the way you are forced. And although the essence of contemplation is passivity and concentration with external objects (and although, as such, it is a total, passive and concentrated perception), in its process there Other factors that, by generating themselves on the subject of subjectivity, are those that give sense and emotion sensory perceptions, that is, what they see in our eyes, listen to our ears, smell our Noses, touch our hands or taste our mouths. So the participation of the viewer, whether active or passive, is always guaranteed. What must, then, have a work of art to induce the viewer to contemplate and not to the rapid visualization with which, often and by force, we are trapped to experience it?

Basically, the power to require the concentration of one of our senses, since only in this way the doors of memory are opened and, as a consequence, of anticipation: the faculty that, together with the sensory perception, It allows man to unify the compositions he contemplates. Thus, if what is involved is painting, sculpture, architecture or any other of the unclassifiable visual arts, the works that will lead us to adopt an essentially contemplative attitude will be those that will take us to fix the view and, Consequently, to learn what we see as a gradual << to be taking possession of >> and not as if it were a purely static perception. And the art that engenders the need to adopt this attitude is, as Susan Sontag says, a silent art, that is, an art that allows not to get rid of attention because, in principle, it has not claimed it , an art that, in practice, annihilates the perceptive subject and an art that, by inducing the viewer to fix the view, moves away from history and approaches eternity.

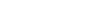

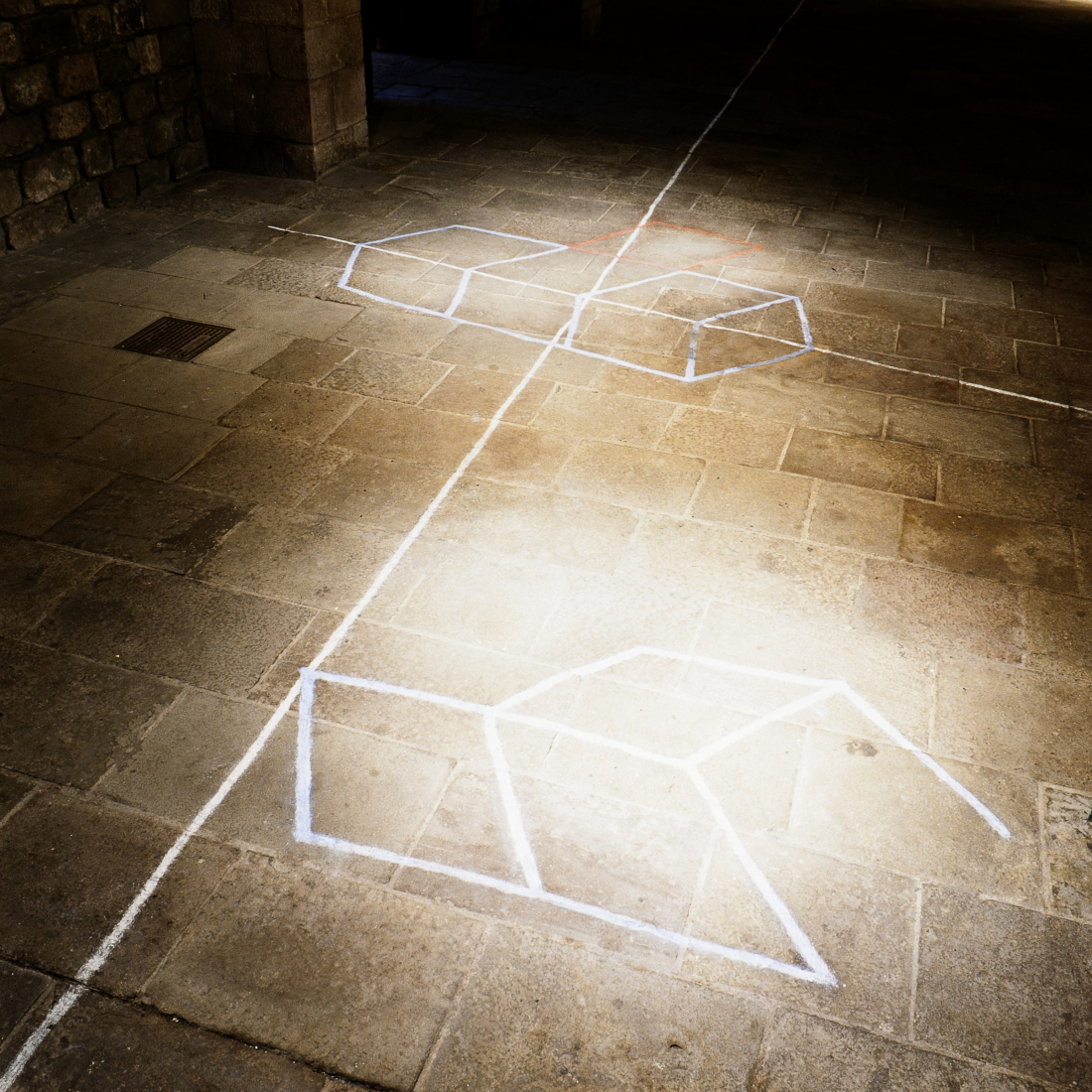

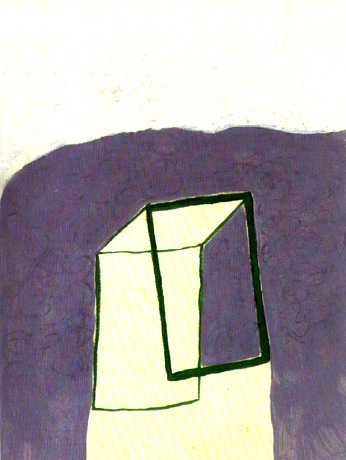

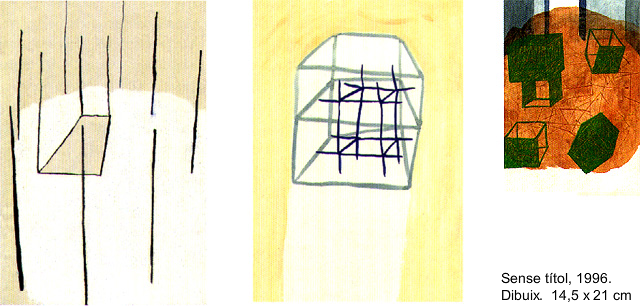

The works of Irene van de Mheen were already made before we arrived. They existed before being watched. And they will continue to exist when we leave. They belong to a time that is not measurable. And they describe their own space. They are like inland landscapes, seemingly flat landscapes but, as we penetrate, we discover volumes that keep us from looking. Landscapes that, when looking at them, although they make our eyes slip over them, reveal in their depth the emptiness of the world where we live. It could even have never been drawn, or that we have been the ones who have done it. Because whoever has the least experience has lived, the ones who have less traveled to them and who has the least respiration. As many others did before; how many others will continue to do it.

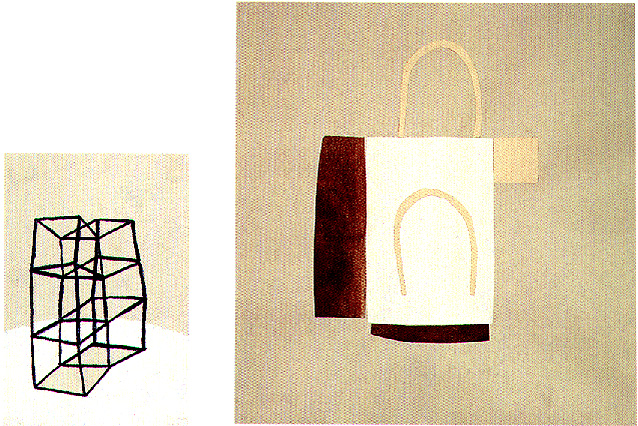

However, despite transmitting, among other things, the sense of silence and emptiness that we have mentioned, the drawings of this artist do not emerge from anything; They start from a very personal investigation around the space in which men move and how this space can be representable or not, in its essence and tridimensionality, on the flat surfaces of a paper, a wall or earth and communicate, at the same time, a real and concrete emotional state. An investigation that, although through history has been treated by creators and irregularly and with unequal intensity, has been and is of great importance in the work of those artists and creators that, like Irene van der Mheen, have He has taken care to reveal the nature of the physical and mental space through which the creative impulse of the artist moves, as well as the existence of the viewer who contemplates it at a distance. All this without shouting from the inside of "an own room" that, like the book and Virginia Woolf, gives the artist the privacy necessary to create his work with complete freedom. From the inside of a room where we, the spectators, will be aware of our dimension in contemplating, from the middle and over time, the depth and beauty of a drawing that, On the four sides, it will make us disappear as if by magic in the hands of an intimacy that does not correspond to that of anybody. With that of anyone who contemplates it.