Solvitur Ambulando

Rubén Verdú (Caracas, 1962). After a residence at the Hangar production centre, he now lives and works in Barcelona. Having completed his studies at the University of Texas and the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) in Los Angeles, he moved to New York to enrol on the Independent Study Program at the Whitney Museum of American Art. His projects have been shown in the United States, Mexico and Japan, as well as in Europe. Exploring the displacement of language, the etymology of tropos and the dynamic shock of aporias, his work records the phantasmagorical profiles of our culture, embodied in the dying logos.

"Solvitur ambulando" is structured into three scenes, which should be read as pauses in the chain that forms Rubén Verdú’s narrative. The piece takes a discursive structure that is characterised by narrative heterogeneity and whose story takes the meaning of tropos as its protagonist. The author focuses on different historic moments and, in each case, the recordings revolve around a conclusion, a Beckettian test of spirit: that the word (logos) is all we have. In short, it is thanks to the word that only human beings have history, cultural development and extraordinarily complex diversity. A project produced specifically for La Capella, “Solvitur Ambulando” is built up from intensely dramatised materials and reading processes.

The title is a Latin expression, used in philosophy and science, which suggests the possibility of resolving a controversy, a paradox, solely through empirical practice: it is solved by walking.Movement is, then, the protagonist tropos in the project. In this respect, the most prominent rhetorical episode in “Solvitur Ambulando” is that of the speeded-up movement of the spinning top that forms the centre of the space. Like the tropos that keep a dying logos alive and animate, is only possible to keep the top spinning through sudden spurts of energy. Similarly, reanimating the inanimate is culture’s necrophilic vocation.

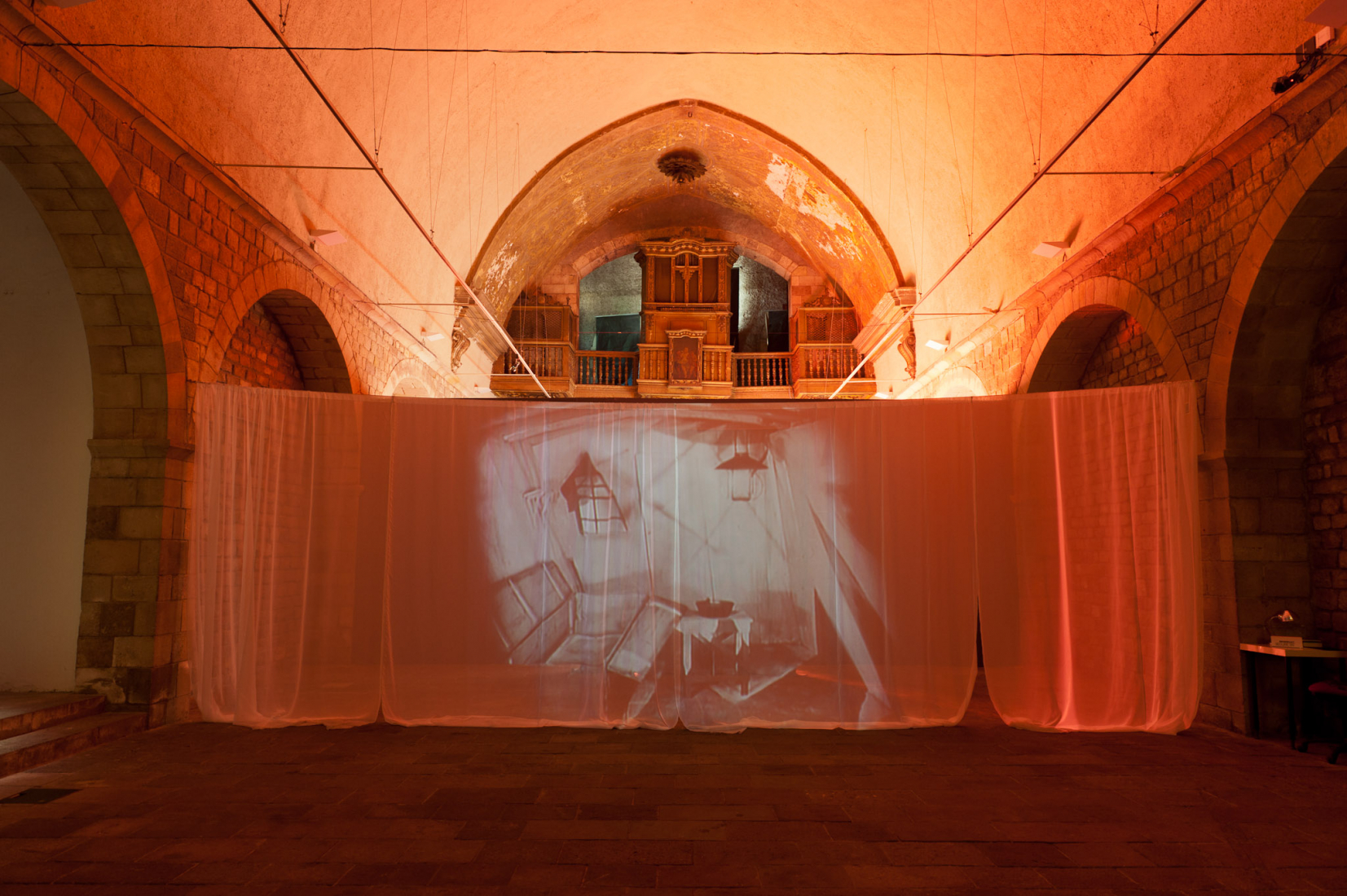

The first scene occupies the access into the room. Spectators have to pass through the curtain on which the first element, Solvitur somnambulando: Holstenwall, is projected. This penetration of the screen by visitors to the exhibition highlights the cinematographic architectural elements that are the protagonists in this project. The tropist element plays a very important role here. By removing human presence from the scenes in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, what we show is an attempt at total architecture that documents different views of Holstenwall, a fictional place. In its finished form, the only moving things are a couple of merry-go-round horses whose movement recalls that of film reels going round, and the shaking and striking of the film by the projector. This, then, is how the exhibition itinerary begins, stripping off the most everyday instants of tropic reanimation. If photography is sometimes considered fundamentally synchronic and its status, therefore, that of a memento mori, what is film but the reanimation of that habeas corpus?

At the back of La Capella are the evaporated volumes of another zombie, those of Solvitur deambulando: Cheval-vapeur (CV), which revolves at around 200 rpm, driven by a one-horse-power electric motor. The perilous indetermination of a volume of this size (225 x 145 x 145 cm) moving at high speed is complemented by two panels that show the contents of a letter sent by Rubén Verdú, informing the Galerie Louis Carré & Cie in Paris of his intentions, and a photograph of the presentation at the same gallery, on 22 June 1966, of Cheval Majeur, with Marcel Duchamp in the background. In this way, it is insinuated that there is a need for in-depth study of the particularities concerning the edition of this sculpture, at which Marcel Duchamp demonstrates his theories with regard to appropriation by adding a revolving pedestal and giving a practically monumental size and a new title to his brother’s work. The evident tropism in this work alludes, once more, to the tropism that sustains the necrophilic economy of culture and ensures its continuity.

Scene Three. In one of the side rooms we can see the tropic movements of Solvitur metambulando: Tropical Ohio. These movements are designed to conceptually cover a broader geographic area, pointing, therefore, to a transterritorial, transcultural and meta-authorial sphere. An edition of four intervened copies of Pavesas, Samuel Beckett’s Spanish edition of short playspublished by Tusquets, is presented to the public, showing the four double pages that contain the complete content of the work. The intervention consists of replacing the contents of the original title, “Impromptu de Ohio”, with the new title of “Tropical Ohio”. “Tropical Ohio” is, precisely, the result of a “translation chain” from Beckett’s original title, and therefore suffers from linguistic deformations accumulated in the succession of different languages to which the text is subjected in translations. The final text is, therefore, qualitatively speaking, something new.

Colaborators

TallerBDN