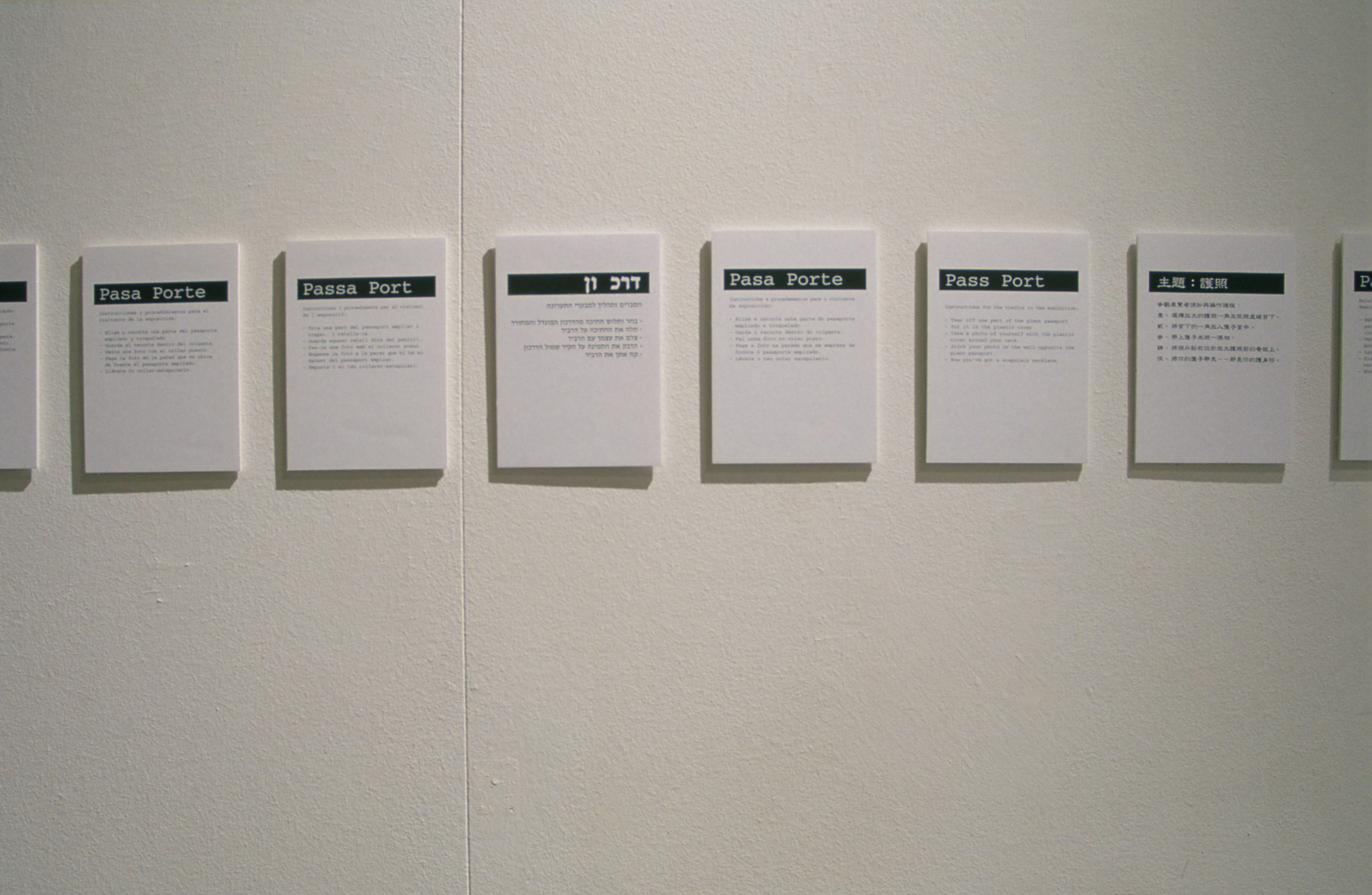

Pasa Porte

PASS PORT. Installation

Emis -young, twenty-eight-reached this Syrian harbour in a Tenian ship,

his plan to learn the incense trade.

But ill during the voyage, he died as soon as he was put ashore.

His burial, the poorest possible, took place here. A few hours before dying he whispered something about "home," about "very old parents."

But nobody knew who they were, or what country he called home in the great panhellenic world.

Better that way; because as it is, though he lies buried in this harbour, his parents will always have the hope he's still alive

In the Harbour (1918), Constantine P. Kavafis

Like the young man who wanted to learn the incense trade in Syria, we all embark on a voyage of some kind. Some of us -not all- perhaps know where we come from, but we are never sure of when or how we will reach the last stage in our personal journey. Like the young man, too, we are perhaps also accompanied by a memory, an emotion, but the feeling of solitude is an inseparable travelling companion on these voyages.

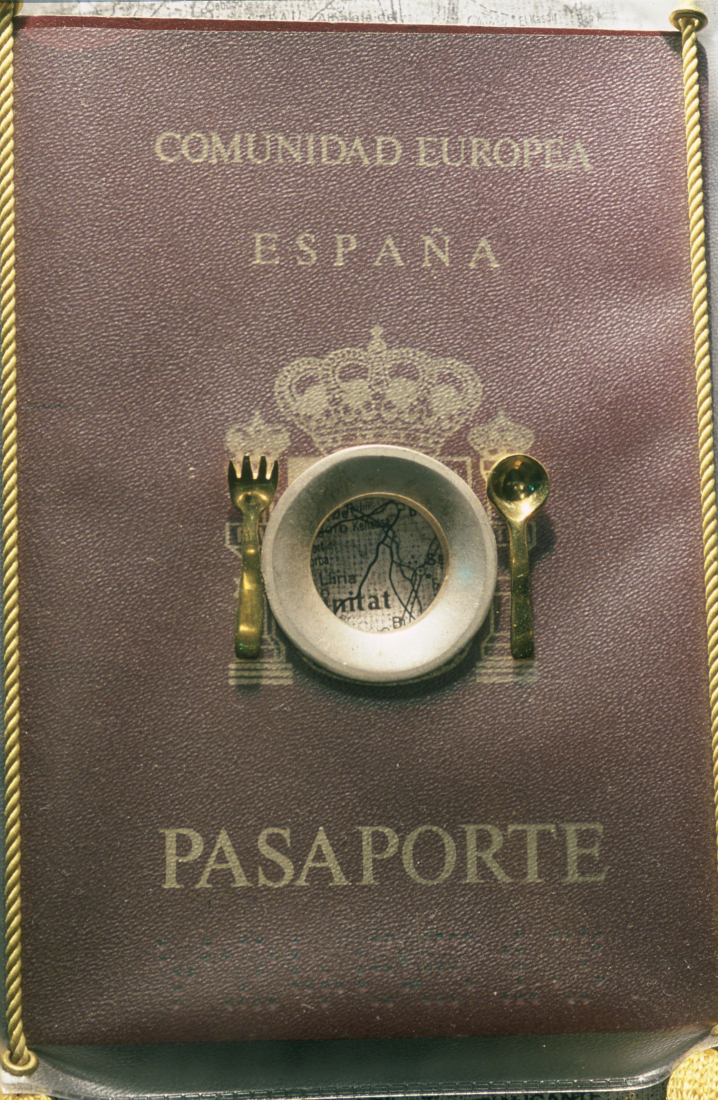

The word passport comes from the Latin passus, 'pace', 'step' or track'. This document, besides allowing the holder to cross frontiers and bridges and to travel freely along roads and through lands, is also a safe conduct giving protection, guaranteeing rights and even safeguarding life.

The work Pass port explores the problem of identity in the heart of a society -western society- in a state of constant mutation. But not an artificial identity of symbols and flags, but one submerged in the depths of human essence. It speaks to us of the false certainty of knowing who we are and where we come from, and of the fear of never finding ourselves, of not recognising ourselves. It speaks to us of coming and going, of the conflict between the need to feel that one has roots, that is, that one belongs to a place, and the freedom to be a solitary nomad. It speaks to us of the permitted and the prohibited, of conventions and artificial black-and-white visions. It speaks to us, too, of the preservation of dignity and rights.

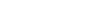

In the installation Pass port, the passport is also, and at the same time, a scapular, a precious, magical talisman that can help us to open up and cross our own inner frontiers. A scapular passport symbolically linking two concepts that are fundamental to the traveller's survival: identity and protection. It takes us back to primitive jewel-making, to the ornament placed on the body and its primordial function of protecting, as it helped to re-establish the original order and harmony between the human being and the universe that surrounds him or her, broken by their actions of hunting and recollection. It is the extension and projection of the individual identity.

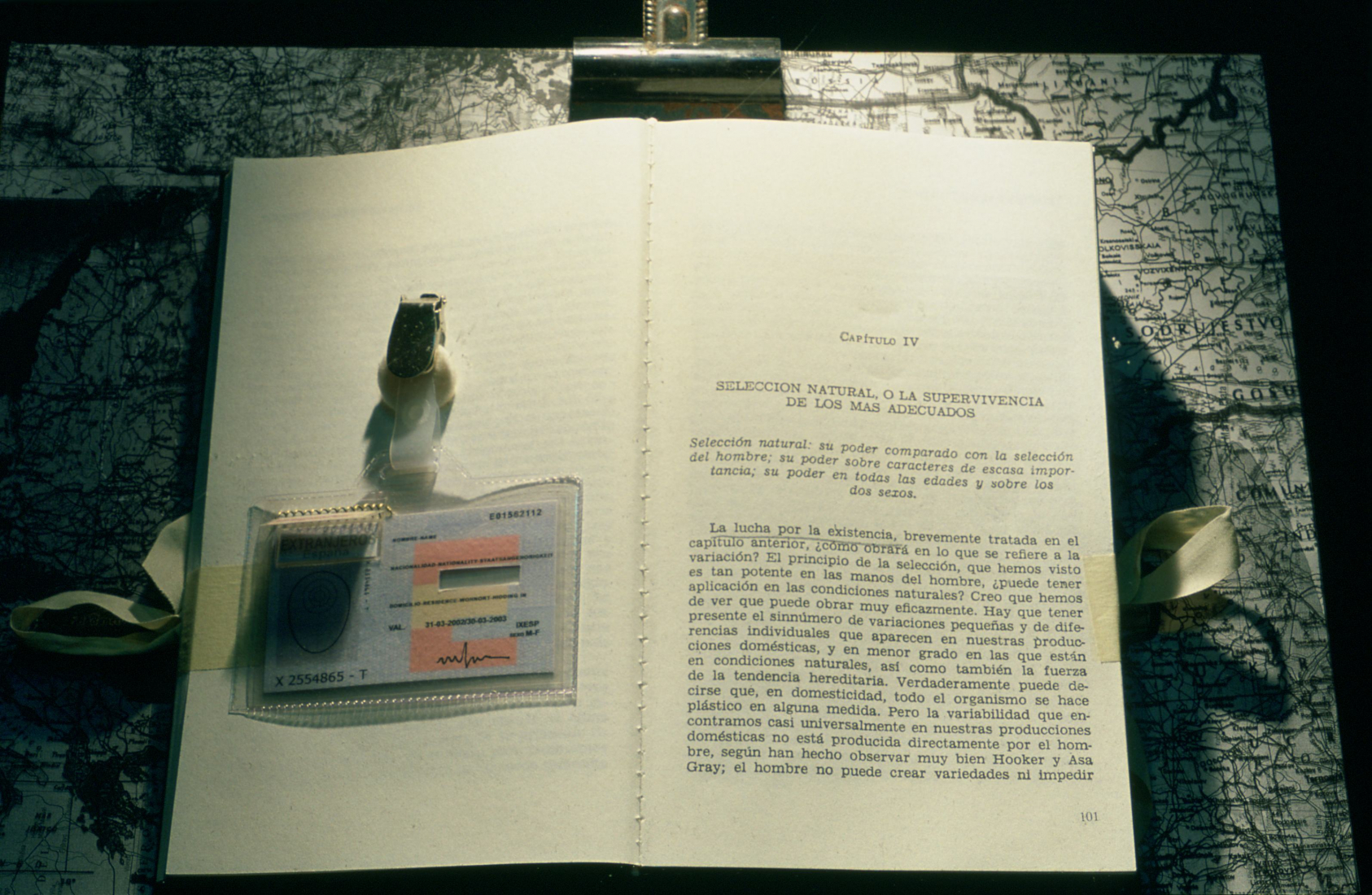

Not without irony, Guigui Kohon proposes a ritual, a magical act: exchanging a fragment of the vague identity embodied in a passport which has been enlarged, punched and cut into pieces, ripping out a piece and replacing it with a tiny fragment of our own identity by taking our picture. The act of breaking up the passport into pieces offers us the possibility of a shared, mixed identity, with broader, more generous, more universal horizons.

Ramon Puig Cuyàs. June 2002

Sponsors: Caja Madrid. Obra social

Sponsoring media: El País i Ràdio 4

Collaborate: Schilling