Realismo

Calculation has always been the foundation on which engineering rests. It is employed to attempt to meet a basic need, which is to ensure the enduring survival of all the structures that are assembled, erected or moved and which defy the irrevocable conclusion of the Second Law of Thermodynamics, the law that simplifies everything to the point of absolute nothingness. Building these complexities and keeping them stable constantly demands tremendous effort because normally they tend to obey the rule of entropic collapse. This ought to be the ultimate essence, the final state of things, shouldn’t it? After the Big Bang, we ought, then, to talk of Perpetual Wear and Tear. Well, no: those things that draw our attention – while they continue to exist, while they last – shape our experience of reality and put on a show of dogged determination. The outcome of this is our sense that the real belongs to the realm of the obstinate.

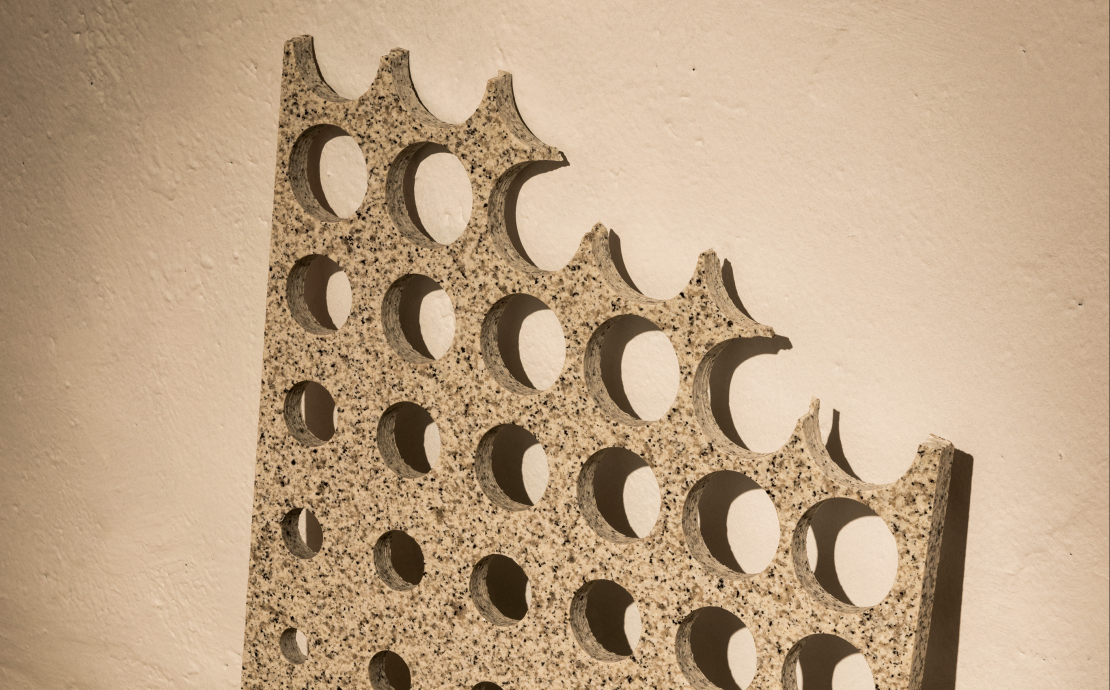

To open this edition of BCN Producció’15, David Bestué invites us to explore a collection of works that he has assembled under the title of Realismo (Realism). ‘Realism’ is a hard, intransigent term. It has been studied in Spain since the early 19th century at the Technical School of Highway, Canal and Port Engineering, situated just a few metres from the Palacio de la Moncloa, the official residence of Spain’s president. Here at the school, courses are taught that combine the rigours of calculus with those of the business sciences. It is not surprising that the combination, in a profession exercised almost exclusively by men and which has turned so many of them into the richest and most influential figures in the country, should have extended so far among the hierarchies of political power and have marked so significantly the historical direction taken by the nation. This intransigent realism, this commodity bought and sold in an exclusive market – in ministerial offices, government departments and in the chairman’s box at some football clubs – has been supplemented in recent decades by an element of unexpected freedom: the computerisation of systems of calculating and the increasingly technical nature of construction. In these new circumstances, it began to throw off the straitjacket of earlier practices and to adopt in its forms a certain air of frivolity that later adapted itself perfectly to the need for a set of symbols keen to demonstrate – so it was said – the country’s progress, though in many cases it ended up exposing the boastful posturing with which the boldness of certain projects was paid. And so, without much thought on the matter by the uninhibited practice of engineering, sculpture was invoked as the formal referent of the experiment, and Bestué, surprised by the discrepancies in the comparison, began to wonder – evidently – whether we ought not to analyse this sudden interest from the perspective of art criticism.

Even though, as he himself says, Realismo points out that in the exhibits “weight, balance and gravity are not represented [but] are” – and that we should take good note of it – the inevitability also leads to a universe containing an amalgam of a series of allusions to assorted ultratechnical worlds and extremely slippery calculations. Sooner or later, we will find ourselves encouraged to take various vanishing lines: archaeology, the speculative paroxysm of history and the construction of the nation associated with it; the body as the unit of measurement of the space and the experience that derives from exceeding the human scale; the consequences of the imposition of standards and the elimination of local variants; the ruination of deserted buildings on the outskirts; and the literary exploitation of the entropic imaginary that characterises the country’s geological morphology. These lines, among others, will help us to discern the value of the post-industrial epic that surrounds us.

David Bestué (Barcelona, 1980) is a key referent for understanding the critical revisiting of the 20th-century avant-garde and formalist movements in recent years, highlighting above all everything related to the decline of postmodern discourses. His exhaustive dedication has led him to extend his explorations into the realm of architecture and – in this case – into the sphere of engineering by using a concept of ‘space’ that ought to be regarded as a ‘prosthesis of the body’. Bestué graduated in Fine Arts from the University of Barcelona. He has had a number of solo exhibitions: Aproximación parcial al trabajo de un arquitecto (Sala Montcada, owned by the ”la Caixa” Foundation, Barcelona, 2005, and Arkitekturmuseet, Stockholm, 2008), Formalismo puro (Sis Galeria, Sabadell, 2010) and Piedras y poetas (Estrany de la Mota, Barcelona, 2013). He has been an artist in residence at Gasworks (London, 2010) and de_sitio (Mexico City, 2013). He has recently published La línea sin fin, a series of fanzines written together with Andrea Valdés.

Planned activities:

- Guided visits to the exhibition with the artist David Bestué

Wednesday, June 17, at 6.30pm

- Guided visits to the exhibition with the artist David Bestué and the architect Robert Brufau

Wednesday, July 1, at 6.30pm

- Exhibition's ending with performance by Aimar Pérez Galí

Sunday, July 5, at 12am

Free activities without booking

Links

Colaborators