Sublime artificial. New art from Mexico

Curated by: Eduardo Pérez Soler and Martí Peran

Minerva Cuevas is a clear example of the orientation that politically committed art in Latin America has taken on. His best known project is Mejor Vida Corp, a company with offices in the Torre Latinoamericana, a well-known skyscraper erected in the heart of Mexico City. Among other activities, Mejor Vida Corp. promotes a series of projects through the Internet which provide tools to resist the effects of globalisation and neo-liberalism. And while Mejor Vida Corp. takes on the appearance of a regular company, its initiatives are aimed at employing strategies, often fraudulent, to break the rules by which transnational capitalism functions. So, for example, the Mejor Vida Corp. website (www.irational.org/mvc) offers, free of charge, labels with false bar-codes to let you buy at cheaper prices in selected supermarkets, or student credentials to get discounts when paying for airline tickets, museum admissions or hotel rooms. With a certain transgressor spirit not lacking in irony, Mejor Vida Corp. seeks to undermine the power of companies in a time of neo-liberalism and dismantling of the welfare state.

In his installation untitled Opener (2002), Abraham Cruzvillegas, offers the culmination of a series of works involving beer bottles, which he initiated with Indio, first presented in the Art & Idea Gallery in Mexico City in 1997. The proposal consisted of an accumulation of thousands of beer bottles scattered over the exhibition floor, making it impassable. The resulting effect was highly suggestive: the obsessive repetition of one same motive - as occurs in some minimalist works, but also on supermarket shelves - bestowed an almost hypnotic attraction on the installation. Spectators could not but feel fascination for such a great abundance of bottles, with their sensual shapes and amber colour. However, they equally experienced a certain sensation of vertigo before the inordinate quantity of bottles assembled for the installation.

The installation (untitled) Opener consists of a bottle-opener hung from the ceiling of La Capella which enables visitors to open the bottles of beer and consume the contents there in the gallery. The only trace that will remain of the public's passing through the exhibition will be the bottle-tops, which will pile up under the opener eventually forming a small mountain. Setting out with a huge economy of means, the piece refers to the vertigo produced by the logic of incessant consumption typical of our age. Finally, the (untitled) Opener installation reminds us of the attraction and, at the same time enormous emptiness of the contemporary merchandise cult.

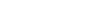

Melanie Smith has for some time been creating diverse series of paintings situated half-way between abstraction and referentiality. At first sight, Smith's paintings fit into the abstract tradition of the New York School, possessing as they do the formal traits that recall many abstract expressionist proposals. Take for example the artist's tendency to repeat one same theme across the entire surface of the picture, like a homogeneous link, reminding us of the all over paintings of Jackson Pollock, or the dense reticula of Mark Tobey. Likewise, the geometrisation of certain of her pieces, as in the Painting for Spiral City series from the year 2002, takes us back to Ad Reinhardt's works of the early fifties. In fact, comparisons between Smith's work and those of the New York vanguard are anything but gratuitous, as the works of both the former and the latter set out in search of sublimity.

It should be pointed out however that the sense of the sublime that Melanie Smith refers to is distinct from that of the US artists. While for the members of the New York School this sense originated in a primordial experience in which culture played no part, in other words it was natural, for Smith its origin lies in the experience of an artificial reality. Despite their essentially abstract nature, this artist's paintings bear constant allusions to the immensity of today's cities and are corresponded by the video pieces Smith has created reflecting the urban landscape of Mexico City. The complex webs that the artist weaves, variegated with a range of different elements, are the result of her fascination for the complexity of the contemporary metropolis.

Damián Ortega proposals base their effectiveness on the search for humour in objects or situations that would otherwise pass subliminally. An author of works of parody, this artist seeks to turn the supposedly sublime into the ridiculous. Thus, for example, in the various interventions in the Power Rangers series, Ortega placed masks representing the characters from the well known cartoon series and which he had bought from street vendors, onto publicly exhibited sculptures by Sebastián, an artist whose works, based on geometric forms, express the aspirations of modernity held by neo-liberal governments. Thanks to the masks, these sculptures took on the form of eccentric robots, similar to those that appear in Japanese comics. The artist rectified, in the Duchampian sense of the word, Sebastián's sculptures, whose abstract purity echoes the constructivist fascination for the sublimity of technological development, by transforming them into absurd caricatures. The case of Transformers (1999-2002) is the result of combining fragments of characters from the science fiction series of the same name with various edible products, such as shellfish, vegetables or fruit. The result is weird, hybrid-looking beings that appear as the parodied reflection of cyborgs, those half-man, half-machine creatures that arouse so much fascination in the contemporary imagination.

Daniela Rossell has gained fame for her portraits of upper middle-class Mexican youngsters who she photographed inside their mansions. They are impacting pictures, both for the generally hyper-sexualized look of the models as well as for the extreme, often kitsch, luxury of their homes. Beyond the interest they possess for documenting the aesthetic inclinations of the Mexican bourgeoisie, these photographs are a testimony of the disproportionate wealth that capitalism can generate in Third World countries. The sumptuous, theatrical spaces - built according to the rules of an aesthetic of excess - that Rossell's characters inhabit allow us an insight into the opulence that made them possible, the result of an economic system based on the relentless exploitation of natural resources and the use of extremely poorly paid labour. As a final comment, Daniela Rossell offers us images of extreme opulence in an allusion to the subliminal nature of capitalism, the economic system that has operated as the driving force in the process of domination over nature by means of science and technology.

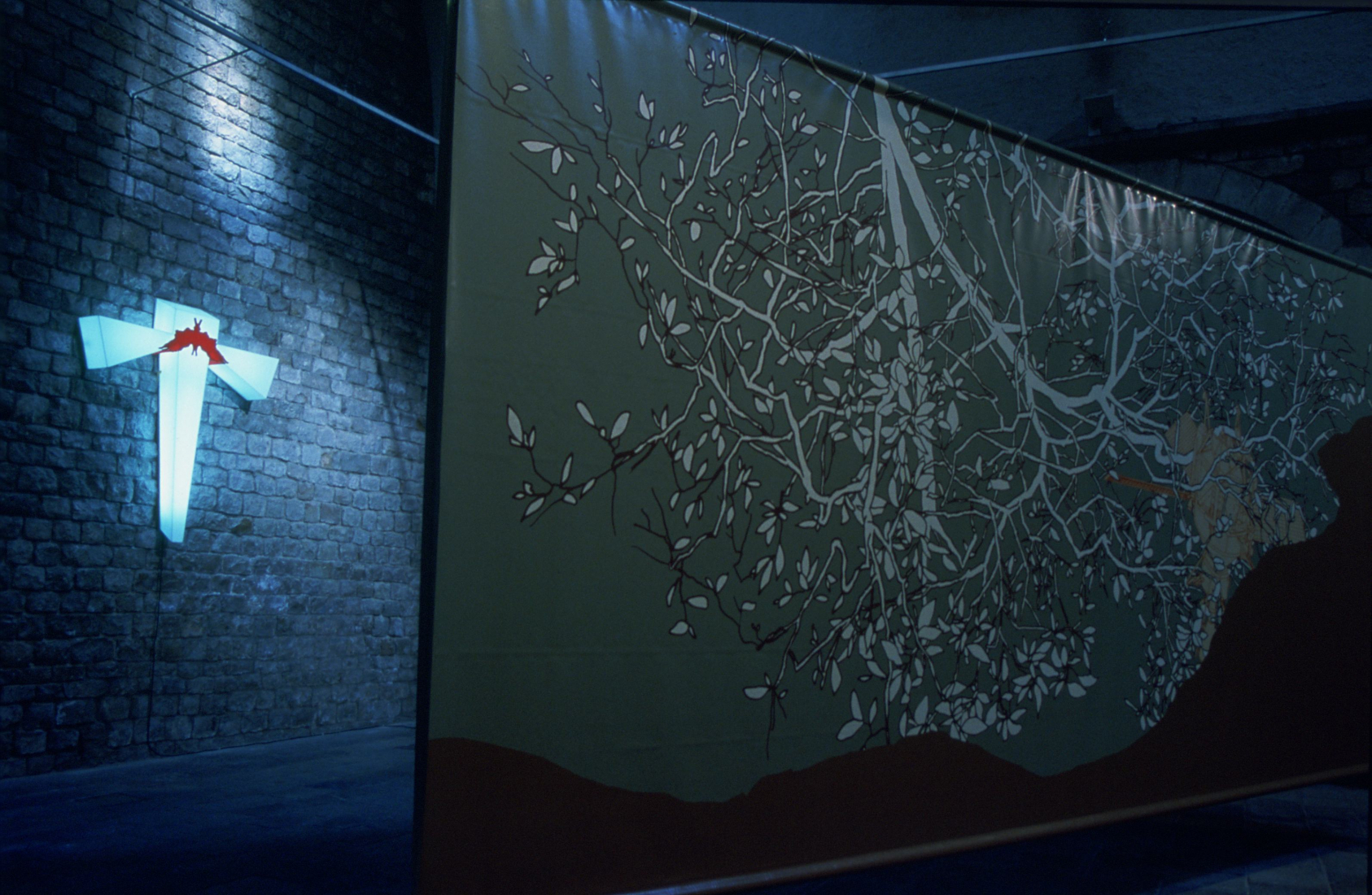

The proposals by Carlos Amorales are inspired in the world of wrestling, one of the most popular forms of entertainment in Mexico. They are works centred on a masked wrestler called Amorales who is none other than the artist's alter ego. The wrestler usually plays the leading part in ritual bouts that allude to the theatrical nature of individual roles in contemporary culture. In Amorales interim, a work from 1997, the artist filmed two hooded individuals with their heads locked together, engaged in a unique wrestling match. In what takes on the appearance of a contemporary bout of sumo, the Japanese martial art, the opponents push each other backwards and forwards, attempting to force each other off the screen, which becomes a kind of virtual ring. The masks the two wrestlers wear are identical, so it may be deduced that they represent the doubles of one, same person, fighting each other. The underlying message that Amorales wishes to emphasise is the amazing capacity of contemporary technology to produce extremely lifelike replicas of reality; duplicates of such precision that it becomes impossible to distinguish them from the originals on which they are based.

Humour is an essential component of the proposals by Rubén Gutiérrez, a creator interested in the products of the culture of the masses. Using icons and strategies drawn from the world of the comic, television and film, Gutiérrez reveals the humorous side of certain contemporary phenomena. So, for Objects over Havana, a series of photographs presented in the year 2000, the artist filmed various Havana water tanks whose peculiar appearance attracted his attention. They were ellipsoid constructions set on circular based prisms of various meters in height. Using electronic image treatment techniques, Gutiérrez erased the base of each construction to create the impression that the remaining upper parts of the tanks were suspended in mid-air. The effect he achieves in the images is highly disturbing: it is possible to distinguish strange objects, like the flying saucers in sixties' and seventies' science fiction films, floating around in the Havana sky.

Rubén Gutiérrez manipulates the appearance of certain objects characteristic of the Havana cityscape, giving them a new, unique form. He does so in a subtle allusion to the social and political identity crisis that contemporary Cuba is undergoing, which is revealing itself in the increasing decadence of the Cuban capital. If the urban transformation which took place in the Havana of the sixties and seventies symbolised the possibility of establishing a socialist regime in Latin America, the ruinous aspect that the city presents today appears as a metaphor of the harassment of communist Cuba. By isolating and labelling certain urban elements of Havana as paradoxical, Rubén Gutiérrez emphasises its ruinous state and thus manages to create a pointed metaphor of the collapse of real socialism throughout the world.

Pablo Vargas Lugo has created a work that emphasises the hallucinatory nature that today's reality has acquired as a result of the overabundance of information offered by the electronic communications media. Based on the collection and juxtaposition of heterogeneous fragments of reality, the artist re-creates a chaotic, delirious world. His proposals, the result of an amalgam of elements of diverse origin - industry, tourism, oriental religions, comics, psychoanalysis and vanguard art - submit us to a kaleidoscope reality that leads us to permanently redefine the notions that make sense of reality. In the end, the eccentric heterogeneity and fragmented nature of Vargas' works appear as a mirror on a world dominated by cultural discontinuities.

Sponsors: Caja Madrid. Obra social

Sponsoring media: El País i Ràdio 4

Collaborate: Schilling, Fujifilm, Estrella Damm, Iberia